Common sense thinks that our ancestors were tied to their land, without going away. Indeed, it’s true that an important part of the French population didn’t move far away. People grew up in a specific area, very different from the modern concept of France. The reality, I mean the environment where the French lived, was more defined by the province: an administrative unit of the Old French regime that was identified by common cultures, and languages that were shared between them.

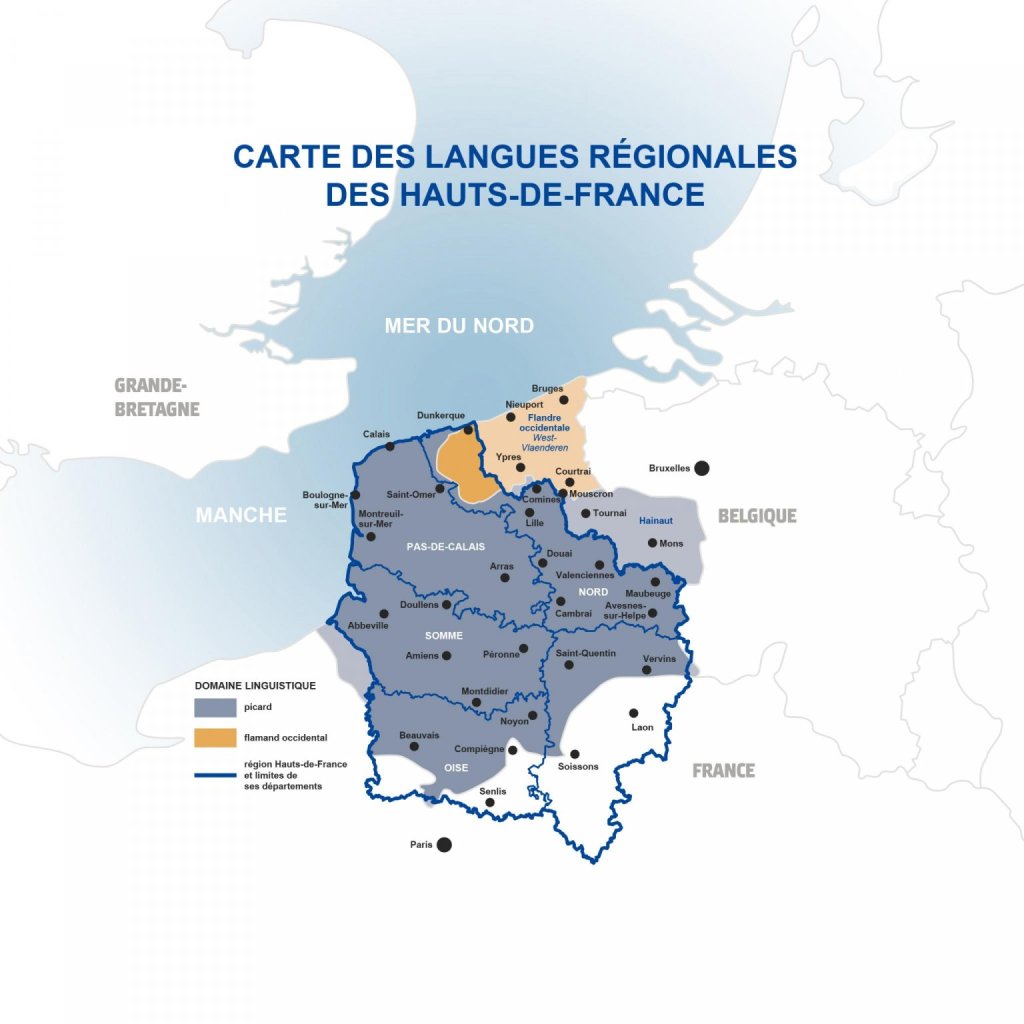

So, in my case, my French family comes from the North of France that is divided into 5 French departments: Aisne, Oise, Nord, Pas-de-Calais, and Somme. Those departments which were born after the French revolution, match with the historical provinces that were on those territories. They were Picardie, Artois, Flandre, Ile de France and Champagne. In this way, it’s interesting to see that, even if my family comes mostly from Pas-de-Calais, Nord, and Somme, they never mixed themselves with the part of the Nord department where Flemish was spoken. In truth, this department that corresponds to the historical French Flandre was multilinguistic: divided between the Picard domain (in blue on the map below) where Picard language was spoken, and Westhoek (i.e., Maritime Flanders, in orange on the map), the part of the Flandre province where the Flemish lived. Hence, my Picard ancestors didn’t mix with the Flemish people, and even if generally, they didn’t leave their villages, or towns from others located in this linguistic area, they often moved inside the Picard domain which covers five French departments and two countries (i.e., France and Belgium, see the second slide).

So yes, in this period people didn’t move a lot, limiting themselves to their provinces. However, this fact applies more to the farmers, and day laborers that were tied to their lands which were their income source, being in a subordinate position with local lords, farmers represented around 80% of the French population at the end of the Old Regime. But if we extend our analysis to other categories of the French Old Regime’s population, we can see some differences. First, merchants and craftsmen had geographic mobility most important, following markets and fairs in their regions. My family for example moved inside the Boulonnais region between Samer, Boulogne-sur-Mer, and other economical centers close to the region such as Montreuil-sur-Mer an important and historical town that inspired Victor Hugo to write The Miserables. In addition, I can talk about sailors and fishermen. Many of them by sailing, established a new life in other ports, more favorable, following the economical situation: for example, I have ancestors from Dieppe, in the Normandy region that came at the end of the 18th century to Boulogne, establishing themselves there. This phenomenon wasn’t specifically for my family: whoever studies civil registration between the French revolution and The Napoleonic period in Boulogne can find many Normans landed from Dieppe. Another targeted category by internal migration in France in my genealogical tree is soldiers. Unlike the military service, which was obligated in France until 2002, the French monarchy didn’t have a military service for all its subjects. Its operation was based more on volunteering with a different process for the militias such as Boulogne where inhabitants were drawn at random to serve in this militia. But in any case, a soldier could be moved far away from his home especially as they were recruited young, without women and children, Thus, I have three soldier ancestors who came from other French regions to the Picardy. They are:

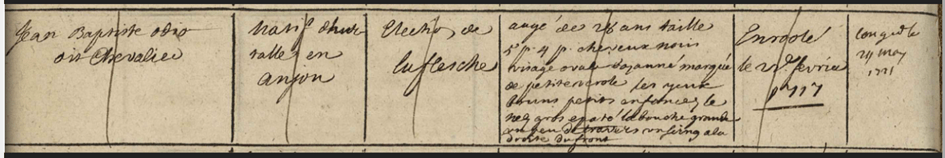

- Jean-Baptiste Audiot (~1689-1739), known as “knight” (i.e., each soldier in the French Older regime army had a nickname), born in Durtal (Anjou), he married in Dunkirk in 1719 to Marie Françoise Dieuset (1692- ?) from Boulogne and died in 1732 in Calais:

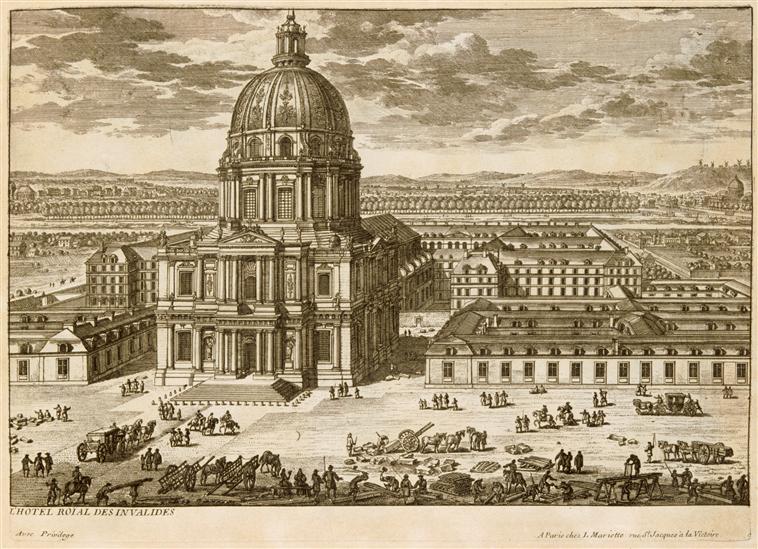

- Veran Chabas (1686-1742) known as “the joy”, was born in Cavaillon (Comtat Venaissin), he was admitted to the Invalid Hospital ( we can see bellow a drawing from the end of the 17th century, and the Hotel nowadays) in 1727, married in 1734 to Marie Madeleine Goyer in Boulogne (1700-1767), he died in the same town in 1742:

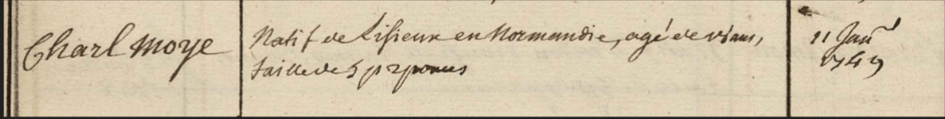

- Charles May (1725-1763), born in Noards (Normandy), was married in 1756 to Marie Françoise Desbaillon (1720-1795) in Echinghen, a village around Boulogne, and died in 1763 in Saint-Martin-Boulogne:

At this point in my analysis, everything seems ok. But as we say, every time we have a disruptive element, and this one is called François Jean Cochon (1660-1735). So let me talk about his incredible history which doesn’t frame in any explicative schemes and that is still a subject of investigation, for 3 years.

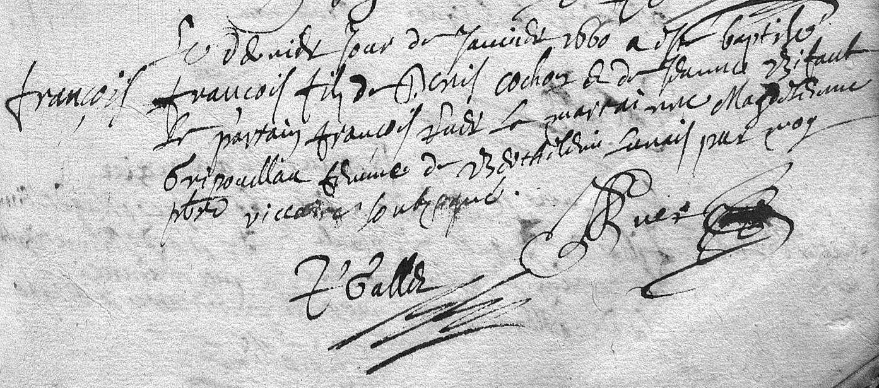

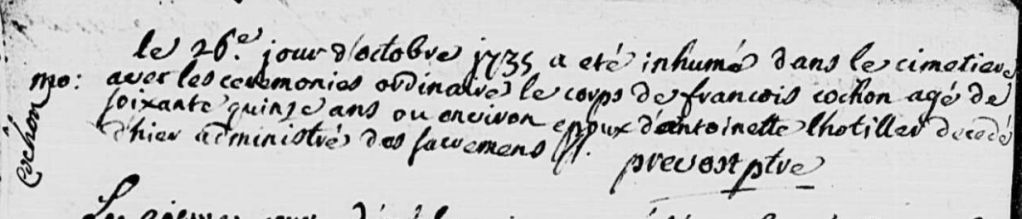

(Saint Symphorien Parish and baptism record of François Cochon [source: 6NUM7/261/249 191/228, Indre-et-Loire Archives])

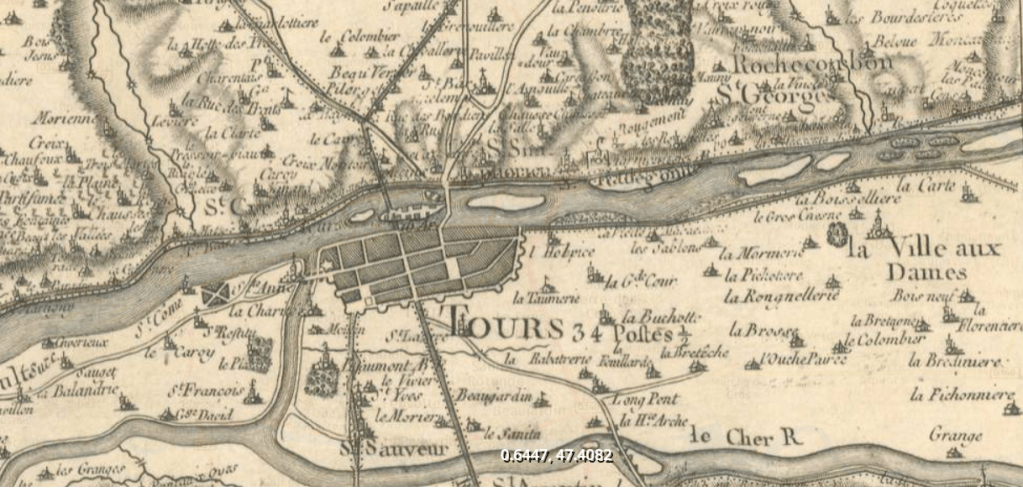

To begin, let’s start at the beginning of his life. François Jean Cochon was born on the 18th of June 1660 in Tours, an important town in the eastern center of France, Touraine province’s capital. François was baptized in Saint-Symphorien parish (image above), son of Denis Cochon and Jeanne Bifaut. I don’t have much information about his family. His parents were married in the same parish on the 28th of May 1645, and he had at least two brothers: Denys, born in 1648, and Barthélémi in 1654. His father probably died between 1660 and 1666 when his wife remarried, but the parish doesn’t have obituary registers. Concerning his family’s social status, I know nothing. By searching other Cochon families we can figure out that they worked principally in the silk industry. In fact, Tours was a center of the French soil industry in competition with Lyon.

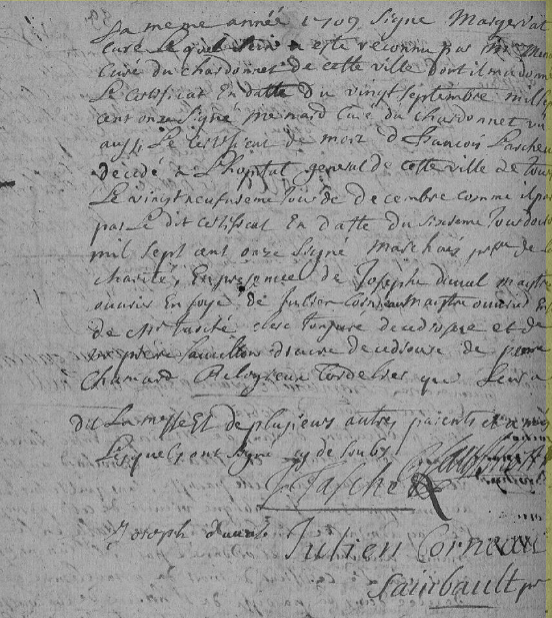

Concerning his personal life, François was married at the Saint-Pierre-des-Corps Parish to Jeanne Rochereau on the 6th of March 1699. From this couple, two children were born: François (1700-1732) and Marie Françoise (1703-1705). His son was the only brother of my ancestor that was capable to have children. He died at the charity hospital; a public establishment founded to carry out those in need. What we can deduct from this fact is that his child didn’t leave our world with a sufficient material existence: He needed support to help him, either due to illness or a lack of financial means.

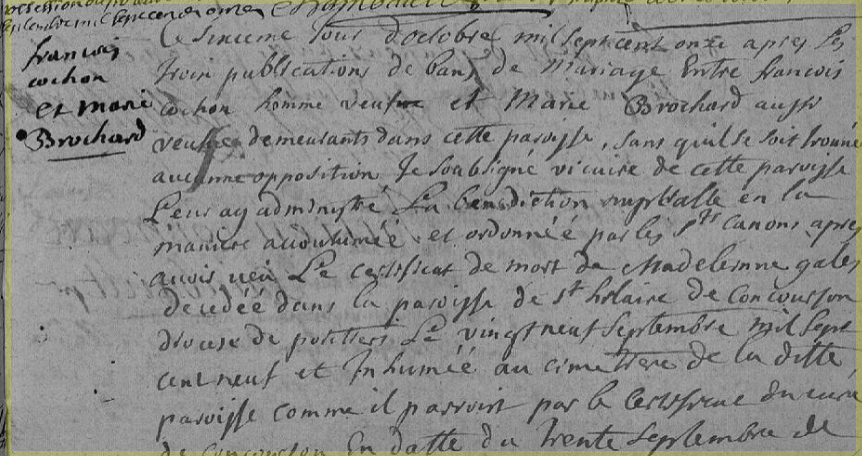

Jeanne died before 1705. In the same year, François was married to Magdeleine Gallais (~1672-1709) (record bellow). From this union, two children were born but didn’t survive. Their name was for both Marie Magdelaine, one was born in 1707 and the other in 1709. In the same year, his wife died but not at Tours. His wife was buried in Concourson-Sur-Layon’s parish, in another province: Anjou. Between Tours and Concourson, 100 kilometers separate the two towns. On her burial certificate, the priest mentioned them as beggars and silk workers. This event wasn’t rare in this period: it was common that poor people moved from one town to another begging for their lives. We can easily find this trend in other French regions during this century. However, the rest of his life did not conform to century standards.

After this tragic event, François had come back to Tours and married Marie Brochard in 1711, in another parish: Saint-Hilaire. At this point in his life, I lost track of him in the archives: I don’t know if he had children with Marie and I didn’t find his wife’s burial, because yes, Marie died, but when? That is an unsolved enigma.

If I can affirm for sure her death, it’s because thanks to indexing archives, I found about 400 km away from Tours, a birth certificate from July 1718 of Reine Cochon, daughter of François. This document mentions her parents’ travel: François and Antoinette Lothelier (~1687-1750), traveled between Sainte-Reine (Haute-Saône) and Beaune (Côte-d’Or). Unfortunately, their daughter died in December of the same year, in a village located halfway between Tours and Beaune. It seemed that this family moved a lot. Even if François was still a silk worker, his economic condition pushed him to do those distances. Maybe he returned to Tours after that Reine passed away, but I can’t prove this fact. In fact, it seemed that between 1719 and 1724, my ancestor Gilles Lievin (~1719-1762) was born. Although his marriage indicates his parish of birth, Vaux-lès-Mouzon in Ardennes, destructions that happened during WWI destroyed parish records.

Between Tours and Vaux, there are around 6-12 days of horseback travel. If our couple had this means of transport, they arrived quickly at this destination. But, if we base our analysis on the time travel between Créancey and Ménétréol-sous-Sancerre, it’s evident that they didn’t have this means of transport. To realize 174km, it took 6 months. How many times did it take for 500km?

On the map bellow, I have illustrated the three main known journeys of his life:

- Red: from Tours to Concourson-sur-Laron.

- Yellow: from Tours to Beaune and Ménétréol-sous-Sancerre.

- Blue: from Tours (not sure) to Desvres.

Afterward, our adventurers arrived at Lillers: a small town located in the Pas-de-Calais department, in the North of France. There, their last known child was born. Her name was Marie-Claire (1724), but she didn’t survive more than 6 days. However, it is important to underline that our couple is mentioned as “going from village to village to sell haberdashery”. Their economic situation seems to be better at this moment. Haberdashery isn’t a distant field from the silk industry. Maybe François took with him his skills and experiences when he worked at Tours and succeeded.

Anyhow, they didn’t come back to Tours. They established definitively themselves in Desvres and died respectively on the 26th of October 1735 for François, and on the 30th of September 1750 for Anne Antoinette, after a full life that took them on the roads of France. Gilles married in 1744 at Doudeauville, near Desvres with Marie Jeanne Picque (1712-1783) and had 5 children known.

So, this family reflects an unhabitual history of France. That of the beggars who roamed the Provinces of the Kingdom, hoping for their lives. However, we cannot reduce this couple to this situation. It seems that they followed a trajectory tied to their professional activities. Maybe, the definitive departure from Tours was motivated by a poor professional or personal situation. According to historians, the revocation of the Edit de Nantes in 1685 by Louis XIV provoked the silk industry’s collapse in Tours. Protestant capitals left the town and many factories closed.

To conclude, when we study family history from now and from the past, we cannot be sure that everyone stayed in our maternal villages since “la nuit des temps” as we say in French. Last technological evolutions have helped to improve the historians’ and genealogists’ work. In fact, without the online index, I wasn’t capable to trace my family to these travel regions. In addition, I hope that future indexation will help me to find other children, Marie Brochard’s death, and the marriage record between François and Anne Antoinette Lothelier that didn’t happen in these regions.